Climbing The Roof of Africa: Mt. Kilimanjaro

This post has been a long time coming. For weeks and then months, and now a year passed, I have been tinkering away, adding little bits here and there. Sometimes memories come to me while I’m painting, sometimes when I’m walking around the city. I find myself acheing to say “asante sana” or “lala salama.” I know it’s silly, but a place can change you. Even after just a few days. I cannot believe it has been almost a year since we drove away from the base of Kilimanjaro, with the most unforgettable week of our lives in the rear view mirror.

Traveling to Africa has been on my bucket list since I was a kid. Like the kid under the blanket with a book and a flash light, I dreamt about walking among elephants and giraffes. I blame it on a love for Mighty Joe Young. I would hear grownups talk about their travels and stories. As I grew older, I learned a bit of various histories in the long list of unique countries, took classes about popular cultures in Ghana and Nollywood. Would work in a gallery among artists from Nigeria, Ghana, Algeria and beyond, having to learn their stories well enough to relay them onto buyers.

We kicked off our seven day trek on December 30th, 2018. With no access to the outside world, we set our sights high for 2020 by climbing to the roof of Africa. Or so we thought. At midnight on January 5th, we made our way to the summit, enduring -15 degrees and 70mph winds, under the stars and sleet. For over seven hours, we climbed the mountain’s glacier under the stars wish sleet blinding our path. Simply by putting one foot in front of the other.

Why would I do such a thing? First and foremost, I have always loved to climb. It was a family activity that ran deep in my roots that grew into a beloved past time with friends back home in Vermont. We were really into climbing roofs and trees from middle school through college. You could say I was on a first name basis with the security guard at St. Lawrence… I also am a low-key adrenaline junkie and spontaneous traveler. When my friend, Cecilia, brought up the opportunity, I’m pretty sure we signed up that day.

As I revisit this post, I find comfort in knowing what I can overcome, both physically and mentally. To find an underlying theme, the importances to breathe and be present. But more importantly, to keep going forward and learning to know when it is no longer safe to do so.

Below, you will find a compilation of journal entries, notes I wrote on the bus leaving the mountain, words I put together on the plane home. The rest have been added over time. It’s a bit of a jumbled mish-mash, but hey, it’s 2020. All photographs are my own unless stated otherwise, with the permission of the owner. The terrain of the mountain was much more involved than anticipated and the weather so severe that I was unable to take as many photographs of our hikes as I would have liked to. To travel is to tap into your curiosity and therefore inform your creativity. The campsites have proven to be as awe-inspiring as the real deal and as a result, I have for the most part captured the campsites and local flora and fauna.

A packing list as well as spotlights on the organizations we climbed for will have their own moments at a later date as they each deserve their own pieces.

I hope you enjoy!

Disclaimer: It’s not pretty.

My bunkmate and fearless leader, Jess Danforth of The Leo Project on New Years Eve

Reflection through a Journal Entry: The Final Day Of Our Descent

The birds are chirping and friendly dulcet tones of Kiswahili chatter, dance around the campsite on our last early morning of our path. It is the seventh day on Mount Kilimanjaro. We end as we began, at a site nestled between the lush montane rainforest and the moorland. The air is cool and damp-encapsulating a dew- like blanket after a long rainfall farewell.

I’m sitting in the mess tent alone as Muhamed prepares our last breakfast together. I’ve been waking up pretty early lately. lol. and decided that although I’m not a journal person, that this would be an in situ, fleeting feeling I would never want to forget. Because of my illness, I have been frequently waking up very early in the morning and enjoying a few moments walking around the campsites or talking with Muhamed before everyone joins us for breakfast.

There are so many things that I want to say, but an underlying feeling takes over.

I know this is all going to sound melodramatic, but I have never felt more free, more present. I have never felt any more myself.

This life here in Tanzania has been unlike anything I have ever experienced.

I would be deeply amiss to not say that I have been humbled and vulnerable and everything in between on this mountain- a place where our thirty-five cooks, guides, porters and many more call home. A home away from their homes, or simply, just home.

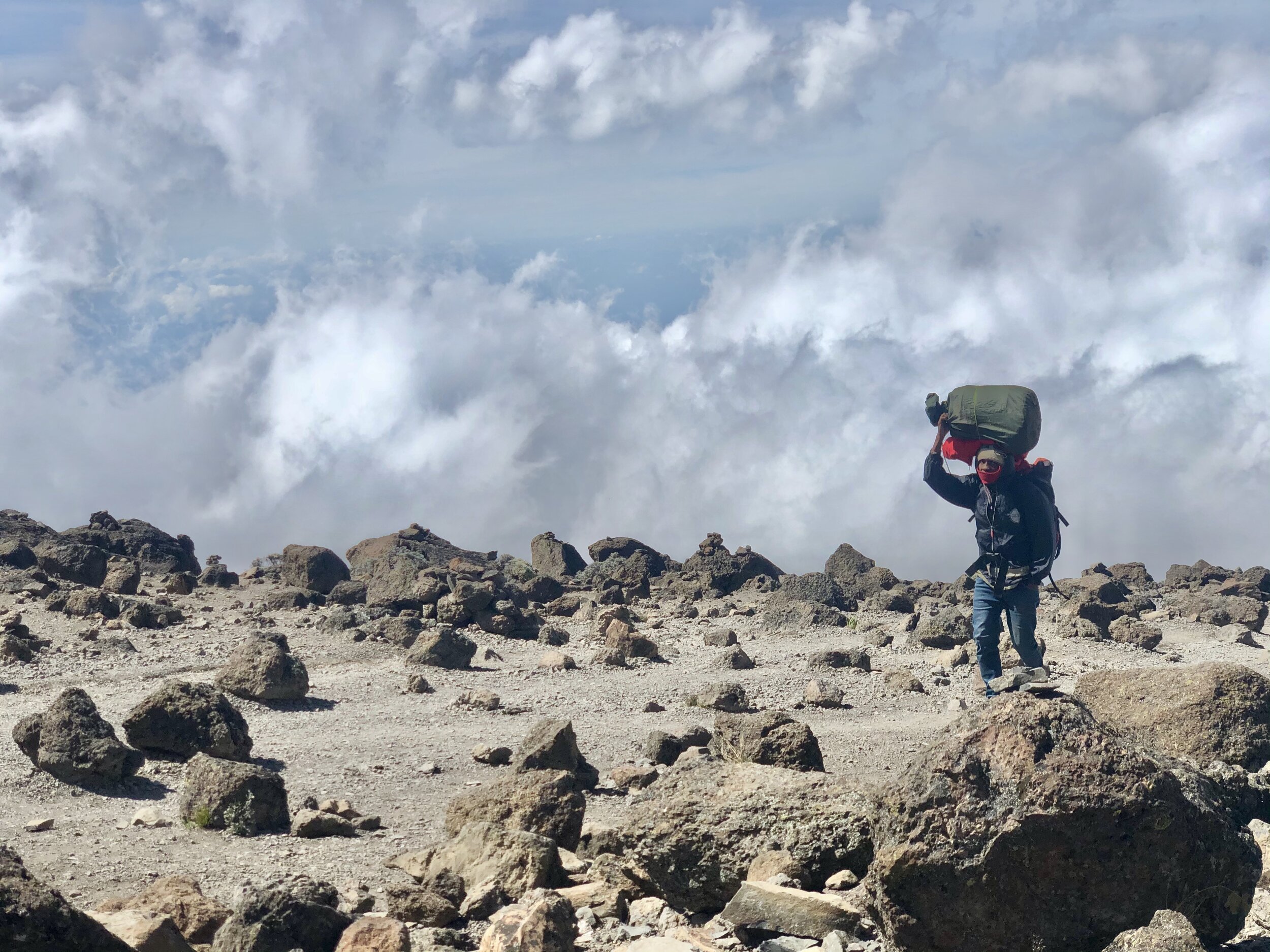

I don’t know if I can ever quite articulate just how incredible these individuals are. The way they move up the mountain, carrying food, tents, our spirits and our successes. It brings me tears to think about their lives and how relative opportunity brought them to where they are now. These types of things make you think. These reflections also make me cringe when I hear “when we get back to normal life.” This is their normal life. This is their home.

It took some time, but I grew to find that I benefited greatly from making efforts to get to know them despite a language barrier. To learn their stories, about their families, what they loved most about the mountain- so even if I didn’t summit, I would at least leave enriched knowing some of the names behind the smiles, the reasons behind joining Maasai Wanderings, a little bit of Kiswahili, some of the names of the flora around us and how the mountain used be a gathering place for local tribes. Warm, big smiles, “Asante Sana” and bear hugs are valuable communication tools, but will never be enough to show my gratitude. Most importantly, through speaking with many of our thirty-five gentleman, I found that one will rarely come across a more inspiring group of people. I will truly miss them.

I am deeply sad that I have to come to the realization that this is the end. As nearby groups sing the well-known “hakuna matata” song, tears come to my eyes once again. This climb has taught me more about myself and what I am capable of- more than I ever imagined. I have never breathed so intentionally, I have never felt such misery, I have never felt so alive. The true marvel of the human body and the fact that there is no such thing as an ego on Kilimanjaro.

Kili is a full ecosystem of five climate zones, flora and fauna seeking balance, weather patterns eager to cleanse and restore and people working together to find themselves up and down the mountainside. I will miss this place, the simplicity of life, the ethereal landscapes and the people who inhabit them.

Our Team

Our smaller group was composed of eight women and one twenty-two year old guy, most of whom I had never met before. Despite the harsh elements, it was smiles all around and we got along beautifully, connecting over the love for the mountain and the reason we were really here- as a fundraising effort to support the creation of pathways out of poverty for children of rural Kenya through our friend, Jess Danforth.

(We would later go on to visit The Flying Kites campus in Njabini and The Leo Project in Nanyuki. These entities each deserve their very own posts. )

Us gals would often tease our new little brother, Chris and thankfully, I was fluent in 22 year old boy. Having him along made me feel right at home. He had arrived a tad underprepared and I was elated to give him my extra down jacket, (I happened to have an extra men’s XL btw), headlamp, neck warmers, snow pants, etc. all of which I had brought with the intention of donating to the crew. Let’s be honest, I also tend to over pack in the event of a rainy day. I gave out glacier glasses, first aid supplies, sweaters, whatever I could spare to make someone else’s experience better. With six siblings, five younger than you, you’re used to sharing.

We would all bond over silly daily things, a deck of Animal Spirit Cards and what we imagined was happening back home at the turn of the New Year.

Although a couple of us had some Kiswahili under our belts (thank you, Duolingo) and the rest of us were doing our best to pick up the language, we found that many of our guides and porters had some seriously impressive English up their sleeves. For those that a language barrier proved to be a bit deeper; warm, authentic smiles and big, bear hugs are the same in every language.

We would also find ourselves remarking on how although we were completely surrounded at all times by men, many of whom we could not properly chit chat with, that we had never felt more safe in our lives. They were the kindest people in the world.

All in all, I can’t imagine going through what we went through with anyone else.

The organization that we trekked with is called Maasai Wanderings and we were led by Julius, Ben, Adi, Oforo and many more. You won’t get any gold stars, uplifting quotes, or luxe glamping opportunities, but you will be under the guidance of best team on the mountain. And that’s honestly, really the best way to do it.

“Shortly after we left the gate, we were welcomed by a family of monkeys- a sign that I felt in my heart that this was going to be a surreal experience.”

First journal entry written night four: reflecting on first few days

Deep in my bones, long before I even booked my ticket, I have had a wash of peace within me. In many ways, a form of acceptance that could be visualized like the meditations we did each morning at the Institute of Ecotechnics. Knowing it was okay if I wasn’t the first one to the top. That has never really mattered to me. It’s okay if I don’t make it up there.

Over Christmas, I kept making jokes to family members that I was okay with not making it to the summit and that I’ll most likely shit myself. Turns out I can be a little self-fortuneteller- eh? So far the latter has been true…haha ah fuck. To my defense, I’ve been sick.

My purpose in coming was to have a little adventure, immerse myself in the mountains for a few days and learn. Learn about these cultures from a primary source- not that of the media or even my African Studies courses way back when. To take in the colors and the fresh air and stories of our new friends. To enjoy life on the mountain among those who call it home. To linger on every moment and be thankful for even the highest of obstacles. Most importantly, to see the work The Leo Project and Flying Kites are doing and meet the sweet second grader I have been sponsoring.

I was never meant to make it to the true summit- I knew this in my soul weeeell before I took my first step. At this rate, who knows what will happen.

My body told me this singular story as well, as the first three days hit me with a bout of food poisoning. Nothing could be kept down and I felt utterly helpless, but I continued on. Against the waves of the storm and made the decision that I was going to be where my feet were. To put one foot in front of the other, even if at a glacial pace. Shortly after we left the monkeys of Machame Gate, I knew something was wrong. I couldn’t breath and a feeling of dread overcame me. There had been so many changes to my surroundings that it could have been anything. However, some of the tell tail signs pointed to food poisoning and the fact that I was the only one who was given a beef sandwich.

I feel so weak.

I am not feeling like myself. This is not the body I’m used to. It’s just a shell.

I only just managed to have my first meal of the hike today.

So I carried on, with one step, and then another step. For twenty minute intervals, I would hike as much as I could before ultimately submitting to being on all fours off trail, violently getting sick. I was “sleeping on the bathroom floor because that’s all that you can wrap your head around” sick.

On the first day, a kind guide named Ben noticed I was trailing behind and stayed by my side. He offered to take some of the weight from my backpack and every moral cell in my body felt unbelievable guilt. “B, my job is to make sure you are successful. Please, let me help you.” “Ben! You have your own pack, I can do it!” Well, I couldn’t. After another bit of time hiking, I gave in and let him help me. I also officially became known as “B.”

For the next several miles and thousands of feet of elevation gained, this rhythmic routine repeated itself. Hike a bit, on all fours emptying every molecular compound in my body, wishing it was over, hike a bit… repeat. It would be like this for the next few days. It sucked.

Perry had been asking us all Disney Trivia and had been keeping us smiling from ear to ear. At one point she asked me a questions and just responded with a projectile vom. It was real cute. She later repaid the favor as she “didn’t want Brooke to feel left out” lol, thanks, Per.

But I did my best to put on a brave face and carry on. Trying my best to be grateful for where I stood and not complain.

Thankfully, we have to go very “pole pole” (pronounced like polé polé which means slowly, slowly in Kiswahili) so I haven’t been trailing too, too behind.

Amy has been calling me, “her warrior.” We are all warriors.

Eventually, after dusk, we made it to our first camp. I had never been more miserable.

After some other symptoms of food poisoning made themselves known, Julius told me that he would have to arrange a guide to bring me down. The symptoms I was showing were also falsely telling signs of altitude sickness.

My perceivable world shattered in my heart at that very instant.

Shira Camp

I hadn’t felt so sick in a very long time, but I also needed to get up that mountain. Birdie had made it up with giardia and who knows what else and carried 70 lbs on her back. If my little sister can do it feeling broken, I can too. Birdie also brought me home from NOLS a brass-like bracelet made by Maasai Warriors. One that she had carried up to the top just for me, for over seventeen days. I found a pair in Arusha a couple of days ago that I am determined to bring up and back home to her.

So I assured our dear leader that it would pass and that I could continue forward. “ I can do this Julius. I have had this at home, it will pass, I’ll get better.” After a short chat about what to expect, he informed me that if I could make it to Shira Camp, there is a road where I can be driven down the mountain. Often times, it is easier to make go up than come down. Due to a former knee injury, this was my best option. On to Shira Camp it was…

Reflecting back on the first night while gazing out the bus window to Kenya:

Throughout the course of the first night, I did not sleep- a theme that would continue throughout the trip. Jess offered to keep an eye on me and I joyfully accepted her offer to be my buddy. Once everything was set up, I sat my way through dinner and listened as the rest of the happy campers eat the beautiful meal prepared and remark on how delicious it was. Remembering how everything was carried up, I started to feel woozy and departed ways. As everyone slept soundly from a first day on the trail, I realized that there would be no sleep for me. In order to not disturb my tent mate, I walked around the campsite, under the stars in a state of ill delirium. Laughter and conversation could be heard from the porter’s mess tent. Unwell, drinking as much water as I could, knowing it would only come up again in due time, I focused on hydration. It was ugly. Eventually, my wandering led to a newfound station— a bed of dried rock, mud and grass, perfectly positioned to act as a comfortable seat. That’ll do. Looking up at the stars, I wished on each and every one of them that I would get better. After hours of drinking and retching, I crawled back in the tent and slept for a couple of hours- perhaps only because I was so physically exhausted.

Cecilia, Alyssa and Inocent

The following day, I told Julius I was feeling better, which was kind of true, but I knew that I was definitely still sick. After we packed up our things, I was introduced to Ema. He would be carrying my day pack for me. Again, a sense of guilt and dread came over me. I barely let my fiancé carry my bags! Ema typically spends his days porting up the mountain. A feat I will never quite gather. However, once he too discovered that he got sick at the gate, he was relieved of his typical duties and was assigned to carry my daypack and water. Although I was reluctant to allow a fellow sick person help me, it was a much kinder task and lighter load than he would have otherwise. Just like the day before, every twenty minutes or so while hiking on the second day, I would find myself on all fours, just off the trail retching my stomach’s contents- to which this point, was mostly water. “B, more maji please.” He would lower my pack and hand me the hose to my camelback as if I was a small calf. Carefully, compassionately.

Maji. Water.

“Pole. I am so sorry. You shouldn’t have to do this for me. You will never know how grateful I am for you. Asante Sana.” I would feel like a broken record, constantly thanking them for each and every way by which they brought me back to life and help me get up the mountain. These kind souls would carry my day pack filled with water, my lunch that I could never quite stomach, some snacks and layers. I would share my provisions with my personal porter, Domician, who would carry my duffel each day on his head.

*Pole, uses singularly means, “sorry.”

Every once and a while, we would see guides carrying their clients… I would make a joke that at least they didn’t have to carry me . . . thankfully to which was well-received and they would jokingly try to lift me up.

I knew that Ema was sick too and it not only made me feel small to know that I couldn’t even carry my own pack, but that someone else who was sick was the one helping me.

“Asante Sana, Ema, Asante. Now it is your turn, you need water too.” We would continue this pattern throughout the day until we finally made our way to Shira camp. In many ways, this sounds all very dramatic, but it was real.

“Ben, how far are we?” I would ask a little too much. “I can’t lie to you, it’s far.” Ben would reply. I was thankful for his honesty. “Ben, my friends back home would tell you that I am very pole, pole on the mountain, but I promise I’m better than this!” I would tell him. He would chuckle. Touché, Ben.

A guide asked our group at lunch if any of us had any medication we could spare for “one of the porters.” I knew exactly who he was referring to… We all eagerly searched our packs for whatever we could find- later all donating absolutely everything and anything we could part with- knowing a bit of the conditions by which these people have very little. Eventually, as the sun prepared for her evening dance down the mountainside, we found ourselves descending to Shira Camp 2. A camp that truly took my breath away. We did it.

*In order to properly acclimate to the mountain, we utilized the “hike high, sleep low” technique. The hike technically be done in a single day from the backside of the mountain, but it is not advised as altitude sickness is not something to mess with and can even be deadly.

After changing out of my rain-clad clothes and getting a bit settled, Julius told us to check out the Shira Cave. A porter named Inocent, found that we were interested in the cave and offered to give a couple of us a geological lesson. I was unbelievably impressed by not only his extensive knowledge of the mountain, down to the the science, but how he was able to share with us in English, evidently a secondary language if not his fifth. Turns out, he was working as a porter to save money to go back to school. My heart melted and broke into a million pieces, all at once.

That night, I tried my best to have at least the soup- a zucchini medley- a potion that I am convinced helped me come back to life. After “dinner”, I taught Jess and Chris a few tricks for astrophotography and together, we spent New Years Eve, bundled up, soaking in our surroundings while our cameras balanced on various arrangements of rocks, absorbing the light of the stars by way of long exposures.

An all too rowdy of an evening for us bunch.

I would have another night to myself, getting sick under the stars- praying to the figurative porcelain gods- in this case, the off shoots of camp.

Of course I made jokes of being one of the few making a mess before New Years.

The next day, in a cloud of rainy fog, we made our way up to Lava Tower.

By the time this third day arrived, I was starting to feel a tiny bit better, managed to carry a lighter version of my pack to Ben’s surprise and pole, pole made my way up the trail. We met an odd fellow who claims to be be Mr. Kilimanjaro, leading a poor pack of sheep up the mountain. A few strapping young gentlemen generously weathered the chilly, damp climate sans shirts. This act of kindness made a few of us giggle and it was a welcome pep in our step for the final push.

I still struggled severely, but was thankful that my breathing was starting to regulate and I could keep a few bites of my lunch down. Just a couple though, to be safe. My body felt physically exhausted from lack of sleep, nourishment and energy, but my muscles never skipped a beat. I was thankful that I had made an effort to do some hiking here in B.C. in the months leading up to it, relying on muscle memory. Not too much, but enough to know my pacing and to be excited at the thought of returning to my love for climbing.

Like a bad punchline to a joke, the infamous Lava Tower was nowhere in sight. For a structure that is supposed to be visibly towering us, with a climber or two scrambling up the side, it was as if it had been erased by the thick clouds around us. It was just like when I had hiked in Banff this past summer.

We had the option to stay for lunch, but eager to evade the rain, many of us made the choice to make the descend to camp. But first, we had to make sure we were wearing the right layering as we continue on through the new climate zone, the highland desert. This was a tedious day where we lost most of the elevation that we gained in favor of acclimating to the altitude. However, this was the day folks started to feel like something was off.

For the next few miles, we would be scrambling over riverbeds and shoots down the steep trail. This was really tough on my knees and a tricky before climbing down to Burranco Camp- the base of the 990ft wall.

Burranco Camp was one of my favorites. I loved how the river led to a Pride Rock of sorts, jetting out in front of us, overlooking the land. We could see Meru from a distance as well as the lights of surrounding cities. It wasn’t THE Meru that Conrad Anker and Jimmy Chin climbed, but it was beautiful and made me smile. A stunning species of Raven danced atop the rocks and these out of this world flora features and trees made it seem like we were on another planet. I lived for these vegetation explorations and wished I had more time for footage.

If the clouds would clear, we could see that we were on top of Africa. After dinner, I chose to meditate on this, sitting on a nearby rock. Never again would I feel as I felt then.

I also found myself waking up early and standing down below at the point to watch the sunrise. I watched a lot of sunrises that week.

The wall was by far my favorite day. Having climbed Angels Landing in Zion National Park, it provided the thrill of climbing, without the lack of stability it required to climb AL. I loved bouldering all 990 ft of it and the collaborative nature of the group. At times, our guides would hold our poles and we would turn to each other for support for those that were more elevation shy.

However, one thing that strongly resonated with me in both climbs, was an overwhelming, physical wash of knowing that my uncle was with me. For those of you who don’t know, I lost my uncle, Robbie Noonan on 9/11. He worked for a company called Cantor Fitzgerald and was on the 105th floor of the North Tower. It changed my life forever on a seismic level. As a dreamer, he always instilled a love for life and is always present when I spontaneously agree to go on wild trips, like precisely the one I was on. He was the biggest goof ball and had the biggest heart. He had worked for Patagonia back in the day and loved ice climbing, hiking, fishing, you name it. He had big dreams of climbing big mountains and never made it to them. Rob even had aspirations for Everest and had a dream of climbing it in sight when he passed.

As a citizen scientist, I philosophically struggle with the inner-dichotomy of ghosts, spirits and guardian angels.

With cautious optimism that a few close calls that I have experienced in cars and from near falls that something must be looking out for me. I chalk it up to laws of displacement and that their souls have to exist somewhere are indeed with us, providing touchstones of feeling when we need them most.

A fellow climber felt her mom on the trip and we loved to ask her to make the weather kinder.

. . .

We would find that altitude is a fickle thing. Particularly after fellow climbers started to show signs of altitude sickness early on. I had to stop taking my Diamox after that first day as I couldn’t keep anything down. Julius told us that he in fact did not like the drug. After a few of us got sick at the end of the first day, he concluded that the drug can make people sick, that he knew the mountain and that Western, foreign doctors, indeed, did not. Go “pole. pole” (slowly, slowly) to drink lots of water and to eat as much as you can.

The reality was, I wasn’t able to take any of medication. Not my malaria pills, my daily vitamin odds and ends or my said Diamox. One thing that I did continue to take was Chlorophyll, a supplement given to me by a friend and recommended by an incredibly wonderful nutritionist we were so lucky to have on board.

What amazed me that despite going off this Western “magical altitude drug,” I did not have a single sign of altitude sickness- except perhaps the lack of appetite. This, however, could also be a result of food poisoning. Another benefit is that apparently people did not produce body oder while taking Chlorophyll- we could all get behind that.

Each day, I put one foot in front of the other. Deep inhale, an even lengthier exhale. Right foot, left pole; left foot, right pole. I have never breathed more intentionally in my life than in these last few days. My movement up the mountain became my mantra. To keep my eyes on the ground below me and to make sure to look back at how much I accomplished. If I were to focus too much on how much I had left to climb, I don’t know that I would have been able to do it.

Be Where Your Feet Are

Shortly after reaching Base Camp, a fellow climber pointed out the “walking dead” of the descenders coming down the mountain. We were in for it, huh?

. . .

A Few Days Later: A Reflection On The Flight Home

The night of the summit will always single handedly be the most difficult day of my life. So far.

Having not been able to sleep due to the loud clattering of the wind against our tents, the whistling of the wind itself, and the accelerated beating of my heart, I focused on my breathing- using pranayama exercises I have grown reliant on to lower the pace of my heart. Calculating in my head the preparations for the glacial ascent ahead of me, I laid there in silence, setting my intentions. Terribly ignorant of what was to come. Nothing in the world could have prepared me for what I was about to endure.

At 11 o’clock trapped in my own head, my alarm started to go off. This was it. With my formerly heated Nalgene and summit clothes at the bottom of my sleeping bag, I pulled out my final layers. I was already wearing four layers in my zero degree bag and additional liner. I had thought that I would sleep in them of them to keep them warm. I warmed them up, but I didn’t sleep.

My fiancé’s favorite saying, There’s no such thing as bad weather, just bad gear, echoed through my brainwaves.

Not dissimilar to the brother in A Christmas Story, we sat in the mess tent, waiting instruction in all of our layers. Looks of delirium, terror and excitement depicted on our faces.

Last minute, I decided to leave my four pounds of camera behind. An ounce in the morning, a pound at night.

After a briefing from our leader Julius, it was time to go.

As I write this, my stomach is dropping simply thinking about it.

Despite all logic, I had hardly eaten in six days. We were to hike up five miles and then down twelve that day. Looking back, I really was not fit for the task.

Outside, a row of headlamps twinkled up the sleeted mountain like fairy lights under the nights’ sky. Below us, you could make out beyond the face, little twinkles of the city below.

We would later find out that it was -15 degrees with windchill on the glacier. The wind? 70 mph. At least.

The clear skies above mocked us as we carefully climbed up an icy, snow covered ridge of the mountain. Sleet sharply beating our faces.

After a spell of time, fighting against the elements, I decided to lower my lamp to around my neck so I could better see my footwork. The wind, however, had other plans and often headed my light elsewhere. I would come to treasure my adjusted eyes and the twinkling light of the stars. I don’t recall the state of the moon.

My contacts began to dry from the wind and sleet, causing my eyelids to want to fall. I had no energy.

We would go in waves, finding shelter behind massive boulders here and there to catch our breaths and consume calories- if you could manage.

Crouched behind a small wall of ice covered rock, I found our team. Julius was telling us the reality of the circumstances of the several hours ahead of us.

This was the worst weather he had ever seen in his over thirty years as a guide.

“Don’t fall asleep. You will freeze to death very quickly.”

“You will need to make a decision. To go up or go down, but you have to do it as a team.”

I even heard down the line, “I don’t want to die.”

Not a single person turned back. He divided the guides and the porters he brought on as assistant guides to each of us in proportion to our capabilities.

We moved onwards.

Noticing that one of our elderly guides did not have any poles, I offered up one of mine. I needed it indeed, but so did he- he had nothing.

Our packs became sails in the wind, trying its best to topple us over with every gust.

Crawling up the mountain with one pole, trying not to slip on ice covered rock, I continued to move forward as if I were ice climbing.

Anchor the pole in front of me. Step, step, step. Anchor, step, step, step. For hours. In the sleet, in the 70mph winds, in the -15 weather.

“Be where your feet are. Follow your feet. Keep moving forward, even if at a glacial pace.” I repeated to myself.

After another hour of scrambling with sleet to my face, I felt another lull in my energy.

“Flem!,” “Flem!” I called, in a momentary cocktail of panic, exhaustion and utter fear. She couldn’t hear me. I had contemplated making a pact; I would go down with her if she wanted to. “Flem!” It wasn’t worth risking my life or serious injury for bragging rights, no matter how much I wanted to make it to the top. Over the war cry of the wind, she still couldn’t hear me. I wanted to cry, I wanted to give up. But I took her inability to hear my voice as a blessing. If she had heard me, I wouldn’t have made it as far as I did.

At that moment, I accepted it as a sign from the universe. What I wanted more than anything was to make it to the top. We had come too far to turn back now.

So up I climbed, taking short breaks to breathe, have a few sips of water and a few bites of nourishment for energy. Because I was going so slowly, I didn’t have as much time to eat as much the rest of the group. This caffeine addict hadn’t had any caffeine. I knew my body. It had been through hell and back that week and wasn’t afraid to speak up when I knew it needed more fuel. But also knew when I had to just keep moving towards the summit.

Ben, my true hero, once again took my bag. He knew my limits and where I stored my provisions. Again, I felt guilty. These conditions were much more severe. He didn’t even have mittens or gloves. He was severely underdressed for this weather.

I found Allison and we bound ourselves to making sure the other one made it up there. She was my girl and there truly is no other person in the world I would have chosen as my summit partner. She is a true wonder and goddess.

Just when I felt like I could not longer move, Allison gasped. “The sun is rising,” she said. The subtle red glow of sun along the horizon gave me hope. I to this day have never seen anything more beautiful in my life.

You can see the sun rise before anyone else in the region when you’re that high up. The way the sun created a warm blanket of pinks and periwinkles on the snow fueled me and distracted me from the task at hand.

Pitifully, we would ask Ben for fuel in the form of gummies and bars in our packs. We felt like helpless babies under the care of our caregiver. I had never felt more small, more broken, more at the call of another human.

Once we reached Stella Point- Julius quickly congratulated us and instructed us to go back down. We made the summit zone- it was too dangerous to continue on. Although three of our climbers managed to make Uhuru Peak (they were also by far the fittest of the bunch) he didn’t advise that we take their lead. Several people had already been severely injured trying to make the final ascent. We had twelve miles to descend down the mountain this morning.

We figuratively kissed the snowy ground before us, took a few photos with our phones and made our way down. The sun had fully risen and the warmth of its rays could be felt all around.

Making our way down the backside of the mountain, I peeled off dust covered layers and look around the other world around me. It was as if we were on planet Jakku, navigating through the gorgeous landscape of the Alpine Desert. Amy caught my arm and together we skid down the mountain by our heels. There was no sense in furthering my knee injuries from snowboarding in the past. I am so thankful for Amy.

Where were we?

From the desert, we found ourselves reaching the Mooreland.

Feeling a tremendous sense of relief as we reached our camp.

Descending the mountain was painful, both physically and emotionally. I found myself trying to avoid conversation of what life will be like when we return to “reality.” This was my reality. I tried to take in the fresh air of the mountain, the way the birds sang and the breeze blew through the trees. Although I didn’t have much Swahili, I lingered on every syllable of the guides talking and walking down around me. I didn’t want to leave. Tears welled in my eyes at the thought of it. Life would never be the same and this experience could never be repeated.

Julius told stories of previous climbers, both that inspired or made us laugh. Fellow hikers joked about how various phrases or camping etiquette would be applied to their lives back home. Perry in particular had become particularly fond of her Camelback and joked that she would keep camelbacks for guests in her fridge for when they came to visit. This had me doubled over laughing.

Even though my knees ached beyond belief and it was the most physically draining couple of days, I was so freaking happy. Similar to that of when Ethan and I drove across country for three weeks to get to BC.

I will miss Mohamed’s friendly nature, his inflections in saying “Karibou,” “Happy more happy,” and “You’re weeeeelcome” and the way he took care of me when I was sick. I will miss Julius’s regal command and stories of previous climbers- everything from Mandy Moore to the gentleman who had to be bound like a pig on a spit after altitude sickness inspired him to throw rocks at the crew…

I will miss Emanuel, “Ema,” his sweet, warm smile and how our friendship grew through a commonality of illness.

While this hike was the hardest thing I have ever done in my life, I had never been happier than on the trail. It pushed me beyond anything I ever imagined and I learned you can never be too prepared. Despite being the sickest I had ever been, I managed to make it to the summit zone and intend to go back someday and make it to the proper peak. It was also an excellent grounding experience for all that was to come in 2020.

About This Hike:

I travelled with Flying Kites and The Leo Project! They are an AMAZING NGOs that foster pathways out of poverty in rural Kenya. I am a proud sponsor of a third grade girl and absolutely loved visiting the school after the hike. Please note that this experience was in no way luxe. You are going to see some tough stuff. There’s no glam, it’s real, real life.

Guides recommend that should you wish to go on a safari as part of a package, to do so after the climb. They receive many cancellations from folks who go on safari and then skip out on the climb altogether. Please make every effort not to do this. If you saw first hand how hard these men and women work, you wouldn’t have the heart to cancel. They are dependent on this as their income and cannot be sustained by these sudden changes. We were lead by the fabulous Maasai Wanderings.

The guides informed us that they LOVE visitors and climbers! Working on Kilimanjaro is a vital aspect of their economy- the more trips, the more wealth that is spread amongst the crew and local communities. Just do not be an asshole.

Get to know your guides and porters- they are a wealth of information about where you’re living those few days as well as about Tanzanian culture. I deeply enjoyed learning about their families, where they lived and why they love the mountain.

Just please be kind, take care of our guides, and bring any extra gear you can manage to donate.